Where has the horse gone? Where is the rider? Where is the giver of gold?

Where has the horse gone? Where is the rider? Where is the giver of gold?

Where are the seats of the feast? Where are the joys of the hall?

O the bright cup! O the brave warrior!

from The Wanderer, Old English Poem. Translation: R.M.Liuzza

Where now the horse and the rider? Where is the horn that was blowing?

Where is the helm and the hauberk, and the bright hair flowing?

Where is the hand on the harpstring, and the red fire glowing?

from The Two Towers. J.R.R. Tolkien

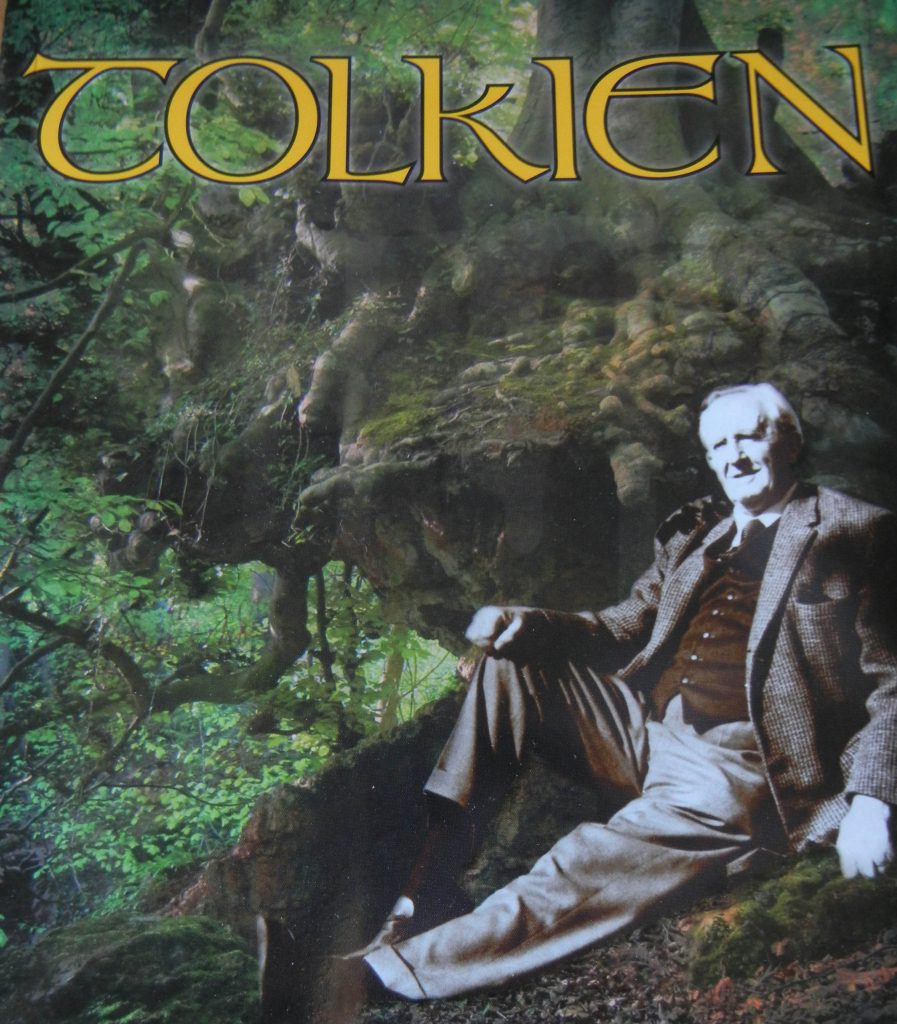

Most fans of J.R.R.Tolkien know that he was not just the author of one of the greatest works of fantasy ever written, but that he was a professor of English at Oxford and, for many years, the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon. He was, essentially, steeped in the language, history and poetry of Anglo-Saxon England.

So it is no surprise that even the title of the trilogy that brought him fame, The Lord of the Rings, is a reference to Anglo-Saxon kings who were warriors, lords, and ring-givers.

My own first encounter with Tolkien’s trilogy took place when I was 14, and although I loved the book and read it more than once over the decades that followed, I did not perceive the thrumming current of Old English history and language that coursed beneath it. That did not happen until I began my own study of the history of England before the Conquest, and I began to recognize Old English words that were familiar from Tolkien’s novels. For example, Meduseld, the great hall of the kings of Rohan, is the Old English word for mead hall. Tolkien first describes it this way, in the words of Legolas in The Two Towers:

“…a green hill rises upon the east. A dike and mighty wall and thorny fence encircle it. Within there rise the roofs of the houses, and in the midst, set upon a green terrace, there stands aloft a great hall of Men.”

The name of that place is Edoras, from, I can only guess, the Old English word edor, which means ‘a place enclosed by a hedge’, just as Legolas describes it. Indeed, the very concept of a great hall comes from the cultures of the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse. And of course there are words like shire (OE:scire—precinct), orc (god of the infernal regions), ent (giant), Mordor (OE: morþor—great wickedness), Deagol (secret), or Isengard (Iron fortress).

Many scholars, in particular Nancy Marie Brown in her recent book Song of the Vikings have written about the Norse/Icelandic elements in Tolkien’s novels; but it seems to me that Rohan is more Anglo-Saxon than Norse – although, admittedly, both societies sprang from common Germanic roots. The name Eowyn, for example, is strikingly similar to the Old English theowen, meaning hand-maiden. And because I cannot read about Eowyn’s exploits in The Lord of the Rings without thinking about Æthelflæd, 10th century Anglo-Saxon warrior queen and Lady of the Mercians, I have to wonder if Tolkien had Æthelflæd in mind when he imagined Eowyn.

My own novels are set in the 11th century reign of Æthelred Unraed (OE: ill-counseled), and the more I learned about Æthelred the more I was struck by similarities to Tolkien’s Theoden. In Old English þeoden means warlord, or king. When first we meet Theoden in the great hall of Meduseld in Edoras (see above), he is described thus:

“…in the middle of the dais was a great gilded chair. Upon it sat a man so bent with age that he seemed almost a dwarf; but his white hair was long and thick and fell in great braids from beneath a thin golden circlet set upon his brow…Slowly the old man rose to his feet, leaning heavily upon a short black staff with a handle of white bone; and now the strangers saw that, bent though he was, he was still tall and must in youth have been high and proud indeed.”

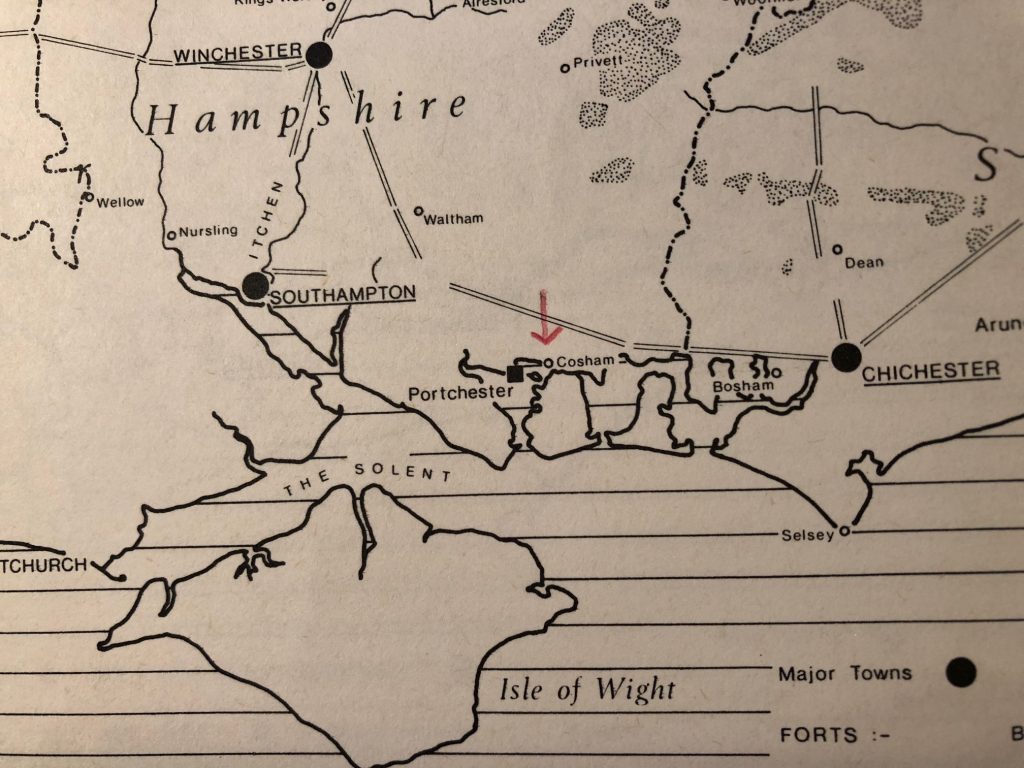

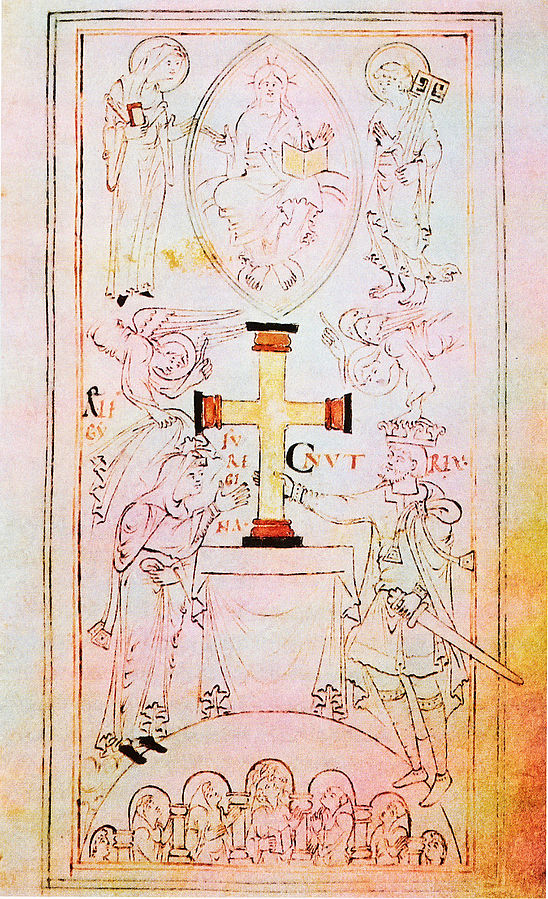

The 12th century historian John of Worcester describes King Æthelred as “…elegant in his manners, handsome in visage, glorious in appearance.” But by the beginning of the 11th century Æthelred is elderly, like Theoden, and has been long upon the throne. His kingdom is being ravaged by vikings as Theoden’s is under attack by orcs. As Theoden huddles in his great hall, unwilling to face the turmoil in his land or lead men to battle, so Æthelred earned a reputation as indecisive, cowardly, and indolent. And like Theoden, he placed his trust in a singularly bad advisor.

Tolkien gives Theoden a counselor named Grima (OE: mask) whose nickname is Wormtongue (OE: wyrm-tunge). A wyrm is a serpent or even a dragon, and Grima is a master at twisting words to persuade Theoden to do his bidding. He is a liar and false counselor who is unmasked by Gandalf.

Æthelred, too, has a false counselor, one Eadric, whom he trusted more than anyone else and whose nickname is Streona (the acquisitor). 12th century historians suggest that Eadric was able to gain advancement by his persuasive speech, and he acquired a reputation for deceit, treachery and murder. It is only when Æthelred is driven out of England to exile in Normandy and presumably no longer under the spell of Eadric that, like Theoden, he finds his courage again and returns to England to lead his armies against his enemies.

Tolkien wrote, in his foreward to the 1966 edition of The Lord of the Rings,

“An author cannot of course remain wholly unaffected by his experience, but the ways in which a story-germ uses the soil of experience are extremely complex, and attempts to define the process are at best guesses from evidence that is inadequate and ambiguous.”

He was referring specifically to theories connecting the wars in Middle Earth to World Wars I and II; but I think his comment can apply to anything that an author experiences – books read, languages learned, emotions experienced. Everything goes into the mind and one never knows what will re-appear, whether intentionally or not, in a manuscript.

My own historical novels, while based on my study of the reign of Æthelred, are very much a product of my own imagination and experience, but I am certain that they owe something as well to my dog-eared copy of The Lord of the Rings.

The road goes ever on and on…

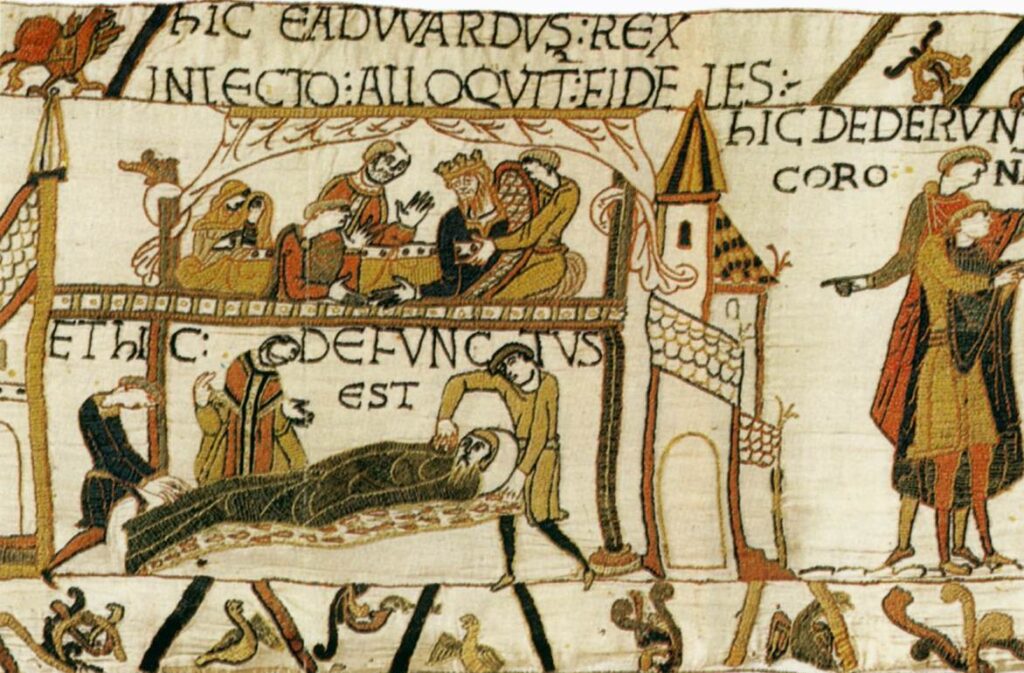

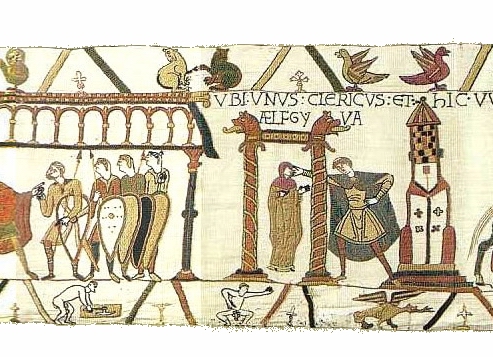

The charming town of Bayeux near the coast of Normandy is perhaps best known for its remarkable Tapestry, a very long length of embroidered linen that portrays events surrounding the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

The charming town of Bayeux near the coast of Normandy is perhaps best known for its remarkable Tapestry, a very long length of embroidered linen that portrays events surrounding the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

On Sunday, June 10, I will be flying down to San Diego to participate in BOOK CLUB BINGO ADVENTURE, an event hosted by Adventures By The Book. I will be one of 22 authors who will be talking and lunching with readers in an intimate setting at the San Diego Public Library.

On Sunday, June 10, I will be flying down to San Diego to participate in BOOK CLUB BINGO ADVENTURE, an event hosted by Adventures By The Book. I will be one of 22 authors who will be talking and lunching with readers in an intimate setting at the San Diego Public Library.

That’s what happened last week when 400 plus members of the Historical Novel Society convened in Portland for a conference. Well, we call it a conference, and in fact there are panels about writing and publishing and history, but in between the panels and the pitches there are dinners and lunches and drinking and, well, it’s a 3-day long party. And a very big party, with writers, readers, agents, editors and booksellers in one place, frequently all of them talking at once.

That’s what happened last week when 400 plus members of the Historical Novel Society convened in Portland for a conference. Well, we call it a conference, and in fact there are panels about writing and publishing and history, but in between the panels and the pitches there are dinners and lunches and drinking and, well, it’s a 3-day long party. And a very big party, with writers, readers, agents, editors and booksellers in one place, frequently all of them talking at once.