Æthelred II, Anglo-Saxon king of England, died on 23 April, 1016. His passing was noted in The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, in an entry that was probably written within a decade of his death:

He ended his days on St. George’s day; having held his kingdom in much tribulation and difficulty as long as his life continued.

Ethelred the Unready, Chronicle of Albion c.1220, British Library (Wikimedia Commons)

Beyond that rather bald statement, we know nothing about the final days of the man who had ruled England for 38 difficult years. What was the cause of his death? Who were the witnesses that stood at his bedside? What words, if any, did he speak before he breathed his last? Any answers to these questions must be mere conjecture—guesses built on what we know of events in England at that time.

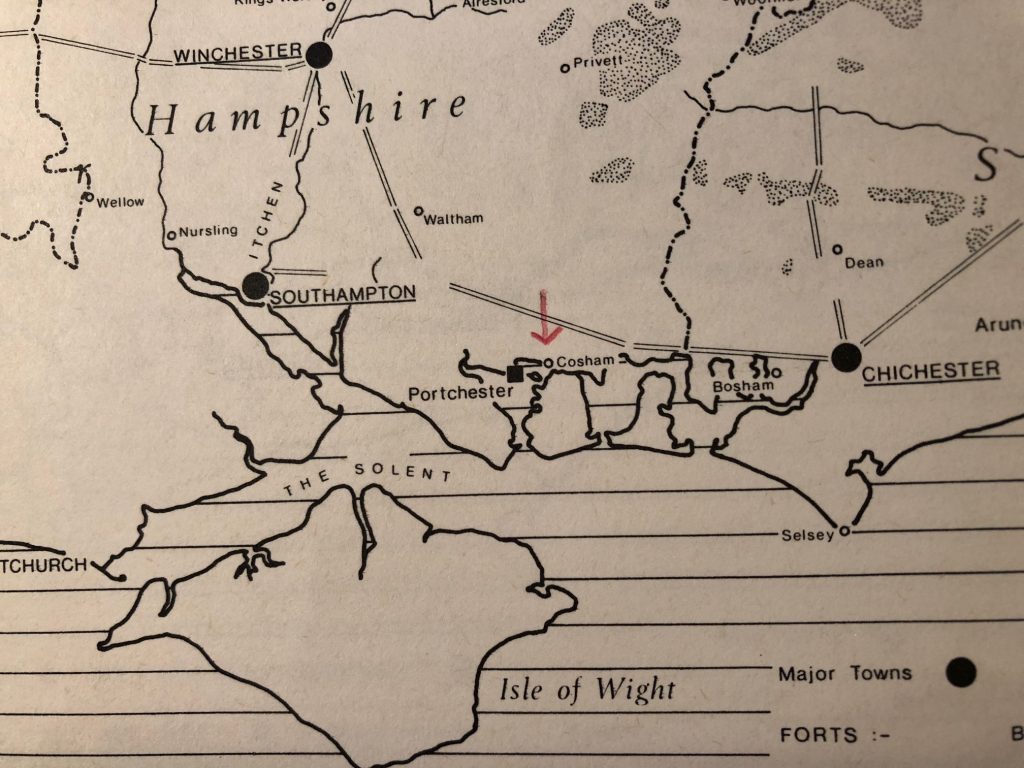

For example, several months before his death, in late September or early October, the king had been taken ill. That the Chronicle actually notes that he was sick that autumn of 1015 is an indication of how grave his condition must have been. Mind you, his immediate forbears were not long-lived. His father had died quite suddenly at about age 34 and his uncle at 19. His elder brother died at 16 and his grandfather at 25, but both of them were murdered so they hardly count. (It wasn’t all fun & games, being an Anglo-Saxon royal.) Nevertheless, at 47-ish, Æthelred was well past his ‘sell by’ date in comparison to his forbears, and any illness would be worrisome. It may have come upon him suddenly, for the Chronicle states that he lay sick at Cosham—a royal estate, judging from evidence in the Domesday Book, but one not previously associated with Æthelred.

As bad luck would have it, he fell sick at roughly the same time that a Danish army led by Cnut invaded England’s southwestern shires, only about fifty miles from where Æthelred lay ill in a manor that was not nearly as safe as the stone walled burhs of nearby Chichester or Winchester. Nevertheless, he stayed at Cosham, apparently too sick to do anything about the invasion beyond ordering someone else to gather a force and respond to it—assuming he was well enough to actually give that order himself.

The king’s health must have improved, though, because after Christmas we find him in London—a journey of about seventy miles from Cosham. Was he well enough to ride there, in the rain or snow of late autumn or mid-winter, or was he borne along muddy roads in a horse litter? Or did he sail to London on dangerous seas along the Sussex coast and around Kent into the Thames estuary? No matter which mode of travel he chose, it could not have been an easy journey and would have lasted at least a week, perhaps longer.

During the early part of 1016 he was recovered enough to lead the London garrison north from the city to muster with an army led by his son, Edmund. Remember, this was still winter, and although it was not as cold in the Anglo-Saxon period as it would be some 400 years later when the Thames at London froze so hard it could be crossed on foot, January was still cold, and you couldn’t count on it being dry. A sojourn with the army would likely have been miserable. Even a tent fit for a king was still a tent. Æthelred did not stay with the army long, though. He soon returned to London, not because he was sick but because, according to the Chronicle, he was afraid that someone in that great host wished him harm. Perhaps he had good reason to be afraid; or perhaps he was just paranoid. Clearly, though, he intended to stay alive. Nevertheless, by April he was dying.

So, although we do not know the exact cause of Æthelred’s death, it may have been that his health, both of mind and body, was failing in the final weeks of his life.

As to who was with him at the end, that, too, must be conjecture. His son Edmund had been campaigning in western Mercia, but suddenly he returned to London. It’s possible that he had received word of the king’s impending death and that he wished to see his father one last time, or possibly he wanted to position himself to make a bid for the throne. Perhaps both things were in his mind. In any case, it is likely that he was near his father’s bedside at the end and that his younger, twenty-something brother Edwig was with him.

Some of the king’s daughters, too, might have been witness to Æthelred’s passing although the Chronicle makes no mention of any of them being in London. Well, actually, the Chronicle does not mention them at all, ever. They were women, you know. Anyway, if the king’s daughters had gathered at the London palace to celebrate Christmas they might have remained within the safety of the city’s walls, given that a Danish army was marauding around the kingdom. Æthelred’s daughter Ælfa had been recently widowed when her husband was murdered by the Danes; did she flee to London after his death or did she barricade herself inside Bamburgh Castle in Northumbria? Her sister Edyth was the wife of a traitor who had joined the Danes. If she was still welcome at her father’s court, she may have been at the king’s side. Their sister Wulfhild was married to a powerful East Anglian lord, but she might have preferred even a bitter, wintry London to the sogginess of the fens, so she, too, may have been at the king’s bedside. Their youngest sister Mathilda would likely have remained in her convent at Wherwell, near Winchester. Nuns didn’t get out of the cloister much.

Queen Emma was very likely among the women who attended the king in his final days. Although there are some scholars who believe that Emma was in Normandy from 1013 until 1017–for she and her children had fled there in late 1013 and the king had joined them for a time–I’m not of that opinion. Emma’s properties and income were in England, so once the king had returned to England and his throne she had little reason to remain at her brother’s court in Rouen.

Certainly Emma’s eldest son, 11-year-old Edward, had returned to England and likely he would have been with his mother at the king’s side. Whether her daughter Goda and her youngest son Alfred were there or had remained behind in Normandy is anyone’s guess. The Chronicle gives us no clue.

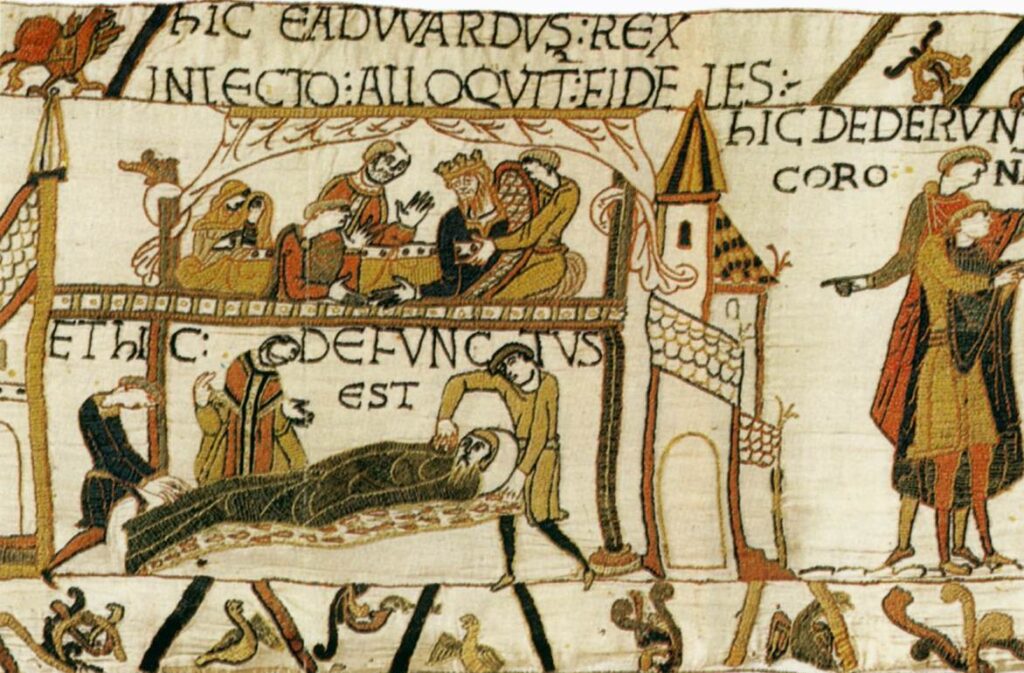

What about the clergy? Who would have prayed at the king’s bedside? The most powerful prelate in the kingdom was Wulfstan, archbishop of York. Because York was already under Danish control it’s possible that Wulfstan had taken refuge in London with the king, especially if the king had been ailing. The Canterbury archbishop, I believe, would have been sent for if the king’s death was imminent, along with the bishops of London and Rochester, and probably some of the abbots who often attended the gatherings of the witan where charters were drawn up and laws formulated. The abbot of Peterborough, Abbot Ælfsy, was close to the queen and had accompanied her to Normandy. I’d bet money that he was in London with the queen when the king passed away. The scene may have looked something like the depiction of the death of Edward the Confessor on the Bayeux Tapestry although I’m guessing that on both occasions there would have been far more people in attendance.

Bayeux Tapestry, Death of Edward the Confessor. Image: Web Gallery of Art, public domain

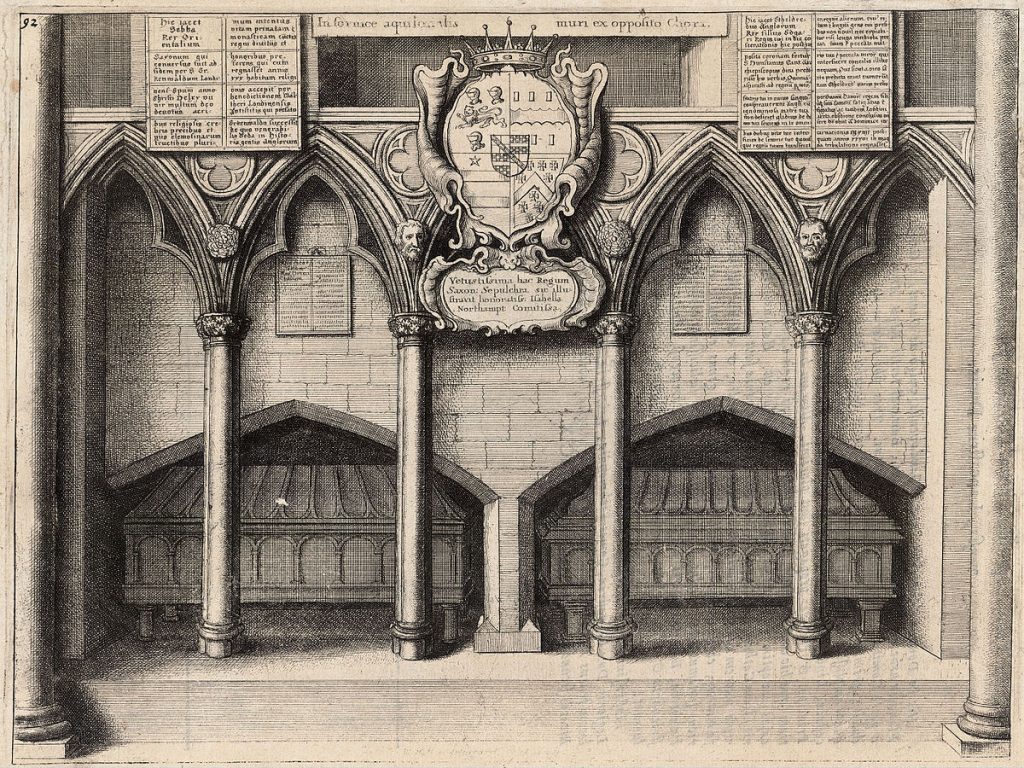

Æthelred was laid to rest in St. Paul’s. The great stone church on Ludgate Hill probably rose high above every other church in the city. It had been re-built after a fire in 962 destroyed the earlier church. It had an elaborately carved wooden ceiling, and buried behind the main altar was St. Erkenwald, the 7th century bishop known as the ‘Light of London’. If you’ve ever wondered who Bishopsgate was named after, wonder no more. It was Bishop Erkenwald. Also buried in St. Paul’s at that time was the recently martyred archbishop of Canterbury, Ælfheah, who had been murdered by drunken Vikings in 1012. Æthelred would have known him well, and perhaps for a time they lay side by side near the main altar. Only for a time, though, because within a decade Æfheah’s remains would be carried in a magnificent procession to Canterbury, and in 1087 St. Paul’s would burn down once again. A new St. Paul’s rose from those ashes, and Æthelred was given an elaborate tomb there, next to St. Sebba, a 7th century king of Essex. That’s Æthelred on the right.

Sebba & Ethelred Monument, Wikimedia Commons

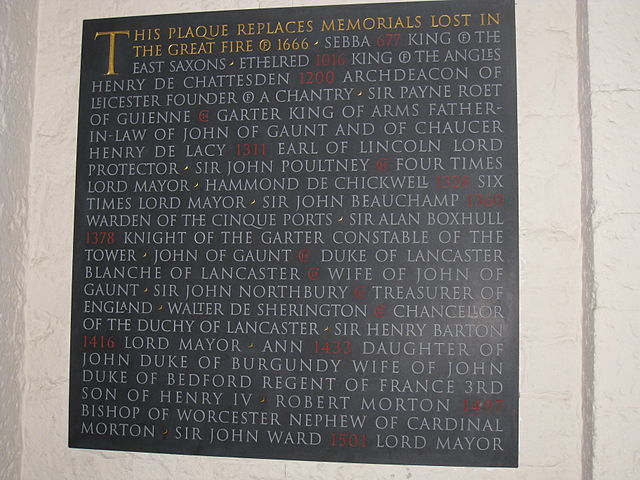

Alas, both tombs were lost when that church was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666, but there is a plaque in St. Paul’s that commemorates them and many others whose monuments were lost.

Photo: Deror Avi (Wikimedia Commons)

In the days following Æthelred’s death, his eldest living son, Edmund, would be proclaimed king by all the counselors and the citizens in London. His coronation was the first to take place in nearly forty years, and despite the Danish army that was terrorizing the kingdom, there must have been an element of hope and exuberance and perhaps relief in the atmosphere of London on the day that the vigorous young king, 27 years old and nicknamed Ironside, took his place upon his father’s throne.

Edmund Ironside. Wikimedia

As for Æthelred’s final words,they went unrecorded. But given the many years that he reigned in the face of repeated Danish assaults, and given the turmoil that he left behind, he may well have expressed something akin to the words that Winston Churchill often repeated to staff during the darkest days of The Blitz: “Keep buggering on”.

Sources:

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, 1997, Anne Savage, trans.

Queen Emma and Queen Edith, 2001, Pauline Stafford

An Atlas of Anglo-Saxon England, 1981, David Hill

www.TheHistoryOfLondon.co.uk, Peter Stone

www.opendomesday.org

I absolutely Love your missives every few months. I am a descendant of Aethelred’s and have always thought the “Unready” part was an unkindness.

Obviously, I snap up each of your books as soon as they are available. Thank you for all of your hard work, and for communicating with all of your fans so faithfully.

Hi Carlene. I’m glad you enjoy the newsletters. I’m afraid that in my books I’ve been a bit unkind to Aethelred. I truly think that he was more unlucky than Unready, but I needed a villain and the rumors (from 100 years after he died) were that he and Emma were not a happy couple. She seems to indicate in the Encomium Emmae Reginae that her true love was Cnut. That’s where I’m headed in the novels.

I am also a descendant of Aethelred, along with millions of others, through his son Edmund by his first wife. I have been working on adding some more details to my Grandmother’s research and found your site and have started reading the book. I’m really enjoying it so far. I have found both positive and negative connotations of the “unready” term in the bit of reading I have done. I’m sure it’s really a mixture of both and really like your interpretation as it gives us a glimpse of what their world could have been like. Thank you!

Hi Gretchen. It’s astonishing that there are any descendants of Aethelred at all. The survival of Edmond Ironside’s infant son in 1016 is really pretty miraculous, and there is a great deal about it that we do not know. It is shrouded in mystery. I’m glad you are enjoying the book. It is Emma’s story, of course, and I was pretty hard on Aethelred, reserving all my sympathy for the queen. If you want a really serious biography of the king, I urge you to read Professor Levi Roach’s recent non-fiction work, Aethelred the Unready, published in 2016. Thank you for posting!

There are many descendants of Aethelred thanks to his son Edmund Ironside’s son Edward the Exile having a daughter Margaret who married the King of Scots – their daughter, Matilda of Scotland married Henry I of England. In this way, all monarchs of England and the UK descend from Aethelred, and all those who descend from these monarchs, so Gretchen is spot on to imagine millions of people being Aethelred’s descendants.

Agreed. AEthelred’s line lived on. What the life of Edmund Ironside’s sons was like remains a real mystery. We don’t know if their mother escaped England when they did or what kind of life they led in exile. But the royal marriage between Matilda of Scotland and Henry I combined the Anglo-Saxon and Norman family lines into the future. Elizabeth II is a descendant of AEthelred.

What do you want me to place in the 3 narrow lines below?