Anyone who tries to write historical fiction about Anglo-Saxon royalty runs into a problem: that would be the names. Many Anglo-Saxon royal names look and sound strange to us today, even if we simplify the spelling. For example: Æthelred, Ecbert, Athelstan – each one seems a mouthful; that is, until you try to twist your tongue around something like Ælfthryth!

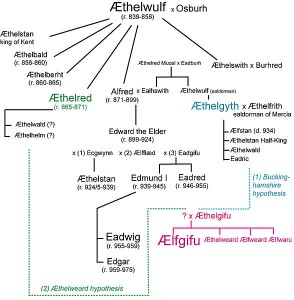

An even bigger problem, though, is that there was a tendency to re-use royal names. Without giving any thought to the headaches this would cause future historical novelists, Anglo-Saxon royalty named their sons and daughters after, well, Anglo-Saxon royalty, so names are repeated generation after generation.

In the time of King Æthelred II, one of the female names we come across again and again is Ælfgifu. The king’s first wife was Ælfgifu. One of his daughters was Ælfgifu. The daughter of one of his most influential ealdorman was Ælfgifu. And to add insult to injury, the king’s second wife, who had the perfectly good, easily pronounceable French name of Emma, was given, upon her marriage, the name Ælfgifu. The name is awkward enough for modern readers, but to have four Aelfgifus in a novel? It’s enough to make a novelist weep.

Still, I came up with ways of dealing with this avalanche of Ælfgifus. To begin with, the king’s first wife is dead when the novel opens. Just a quick mention early on and whew! One Ælfgifu down. The king’s daughter is just a child, so after inserting her full name for propriety’s sake, I switched to a shortened version and called her Ælfa. Two down.

When it came to the ealdorman’s daughter, I decided to use another form of the name, and so the third Ælfgifu became Elgiva. How does one pronounce it? It should rhyme with another, more familiar Anglo-Saxon name: Godiva. Did the Anglo-Saxons say it that way? Probably not, but I’m invoking Poetic License, which I keep close to hand here in my desk.

As for the fourth Ælfgifu, I decided that, in my novel, the king’s new wife would hang on to her French name. It’s true that granting her the name of a royal, Anglo-Saxon saint would have been a symbolic way of identifying her with her new family. (That shouldn’t seem strange to us – it’s done today. Elizabeth Bennett marries Mr. Darcy and becomes Elizabeth Darcy. Welcome to the family.) In documents of the time Emma’s name is sometimes written as Ælfgifu Emma, so Ælfgifu may have been a name used only formally. It’s possible that among her close friends and her family group, Emma remained Emma.

But why, you may ask, was the name Ælfgifu so popular in Æthelred’s reign?

The answer: it was because of Æthelred’s grandmother, Saint Ælfgifu, also known as Saint Elgiva of Shaftesbury. And guess what? Today, May 18, is her feast day.

She was the first wife of Æthelred’s grandfather, King Edmund (and there’s another one of those repeating royal names). She gave birth to two sons: Eadwig who would one day marry a lovely girl named Ælfgifu (stop already!); and Edgar who married – oh dear, let’s not even go there. After the birth of her sons, this Queen Ælfgifu decided to leave the hectic life of the court for the more sheltered life of a nun. Okay, probably she was dismissed/set aside/ retired – a political liability perhaps. Her husband, King Edmund, remarried, although his second wife had no children. It was St. Ælfgifu’s sons who would eventually rule in England.

As a queen St. Ælfgifu was known for redeeming condemned men, for clothing the poor, and for giving property to the abbey at Shaftesbury. She must have been popular there. As a n un, she suffered stoically from ill health. She died in A.D. 944, two years before her ex-husband, the king, would be stabbed to death at a place called Pucklechurch.

un, she suffered stoically from ill health. She died in A.D. 944, two years before her ex-husband, the king, would be stabbed to death at a place called Pucklechurch.

And so today we honor St. Ælfgifu, or Elgiva, if you prefer. She does not appear in Shadow on the Crown. Oh no. If you have read the book, you will know that the Elgiva I have created for my novel may be many things, but saint is not one of them.

Facinating and fun to read! You are a fine bloggeress. So enjoyed chatting with you last night at our Mystwell Book Club meeting. Goddesspeed with Draft 2 of Book 2!

Aelfgifu the nun was healed of an eye tumour. She attributed this miracle to the intercession of St Edith of Wilton, whose veneration she promoted when she became Abbess of Wilton in 1065. Aelfgifu died in 1067.

William of Malmesbury relates this tale in his Life of St Wulfstan, who became Bishop of Worcester in 1062 and was the last Anglo-Saxon survivor of note, remaining bishop till his death in 1095.

In the preceding scene, the guard-captain behind Hakon is Alan Rufus, commander of the Bretons in Normandy and subsequently England. He would have known a famous Wilton nun, Muriel the Poetess. Wulfstan and Alan allied successfully against the Norman magnates during the Rebellion of 1088.

Greetings Geoffrey! Aelfgifu the nun is an Aelfgifu I have not run across before. They must have been legion. There is one on the Bayeux Tapestry, and no one knows for sure who she is or why she’s there.

The best source for the Aelfgifu eye-healing episode is Goscelin of St Bertin’s “Vita Edithe” (Life of St Edith), written around 1080. Goscelin was at that time Chaplain at Wilton Abbey, and was secretary to Herman, Bishop of Sherborne (Wilton and Salisbury) who was in England as King Edward’s chaplain before being appointed Bishop of Ramsbury in 1045. Herman received became Bishop of Sherborne between 1062 and 1065 and died 1078, so Goscelin is a contemporary source for Abbess Aelfgifu’s life.

Incidentally, Bishop Herman had lost the abbacy of Malmesbury due to three monks’ objections and Earl Godwin’s intervention with King Edward, but was accepted as Bishop of Sherborne by Harold Godwinson.

Gunhildr, King Harold’s daughter, was an adult at Wilton Abbey when, according to William of Malmesbury’s “Vita Wulfstani” (Life of Wulfstan), written towards 1120. Wulfstan, Bishop of Worcester, visited Wilton and heard that Gunhildr (“Gunnilda” in Latin) was suffering a malignant tumour and had lost her eyesight. He made the sign of the cross before her eyes and she was immediately healed. Wulfstan is attributed many healing and life-saving miracles and was canonised in 1203. He is patron saint of vegetarians.

Thea Thorsen’s “The Cambridge Conpanion to Latin Love Elegy” places Muriel most likely at Wilton, whereas Hollie Canatella’s article (https://ir.uiowa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1927&context=mff) cites evidence that Muriel was at Le Ronceray in Angers. The leader of the cathedral school at Angers was the Breton poet Marbod, before he was appointed Bishop of Rennes in 1096. One of Baudri of Bourgeuil’s poems to Cecilia indicates that Muriel was originally from Bayeux.

The mid-11th century cathedral school at Bayeux trained many notable Canons: for example, William of St Carilef (Bishop of Durham), Thomas of Bayeux (Archbishop of York) and his brother Samson (Wulfstan’s successor as Bishop of Worcester). Someone asserted that another Bayeux Canon was Alan Rufus’s brother Richard (listed as the fifth son in a charter by their parents).