“I was young and I was foolish and I was arrogant and I was never able to resist a stupid impulse.” UHTRED. The Pale Horseman, Chapter 5. Bernard Cornwell

That about says it all, Uhtred. In Episode Six our hero scores a hat-trick of stupid impulses and manages to alienate Alfred, Mildrith and apparently even his buddy Leofric.

Poor Uhtred!

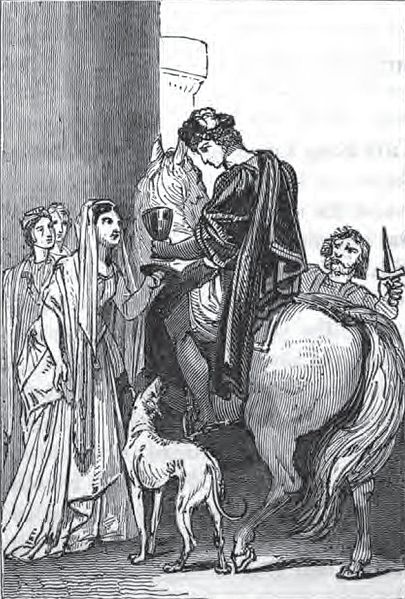

But it’s not all bad. He finds treasure hidden in a midden, he gets the church off his back (briefly), and he gets a new woman, Iseult.

For viewers who have not read Cornwell’s books, I hope you have realized by now that when it comes to women, Uhtred is the James Bond of Anglo-Saxon England. There’s always another girl in the wings.

But poor Mildrith! She seems to visibly fade beside this exotic shadow queen in the gorgeous gown who arrives with Uhtred from Cornwall.

Iseult is a gwrach – a sorceress, who tells Mildrith “You are no longer part of Uhtred’s path.” Ouch.

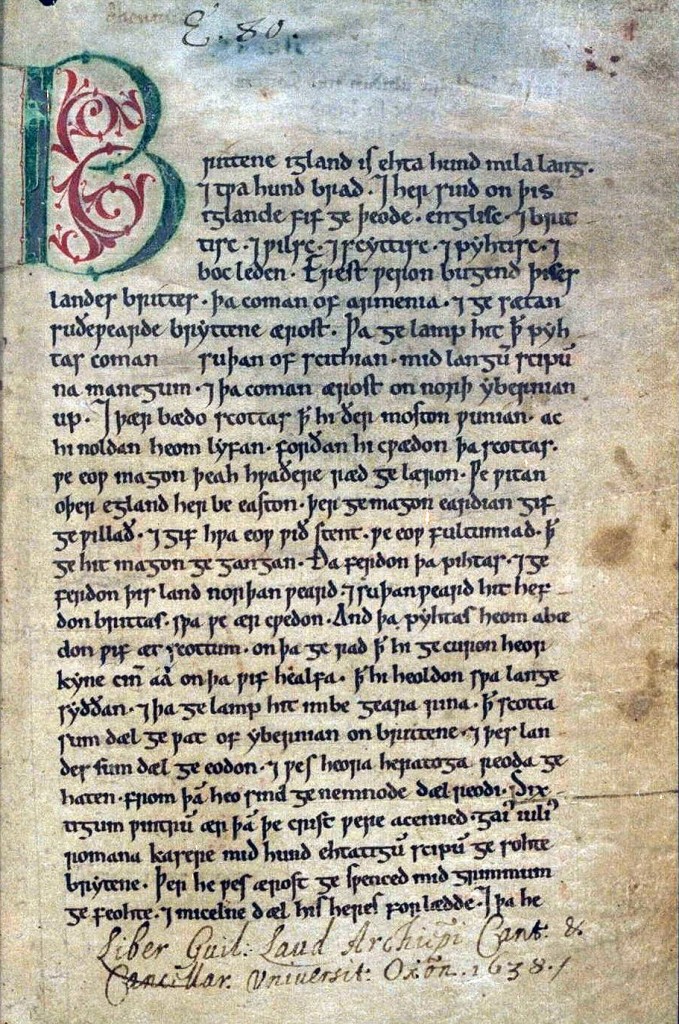

Mildrith, though, is tougher than she looks, and writer Stephen Butchard has done a fine job of revealing the depth of her character in these few brief scenes. She sends Uhtred to sleep with the goats, and then like Brida she’s smart enough to cut her losses. She determines to find a new protector since her husband isn’t willing to do the job. By the way, divorce was acceptable in Anglo-Saxon and Danish cultures. Their kings frequently practiced serial monogamy – one wife after another as necessary, even after Christianity had taken hold.

Another character who is given a bit more depth in this episode is, surprisingly, Æthelwold. He is still something of a buffoon, but he takes quite a risk in tagging along with Uhtred on his lawless adventure to Cornwall.

So, what does Æthelwold hope to gain by siding with Uhtred, and what does young Odda hope to gain by siding against Uhtred (besides, possibly, Mildrith)? Well, King Alfred is not in good health. If he dies, it is not his infant son who will be placed upon the throne by the witan, but a warrior who has proven his ability to lead men. Young Odda seems to be attempting to place himself in that position, and he doesn’t need a warrior like Uhtred standing in his spotlight, so Uhtred has to go. Æthelwold also recognizes Uhtred’s skill as a warrior and seems to understand that Uhtred may be of use to him if something should happen to Alfred. The stakes for both men are high.

While in Cornwall Uhtred runs into King Peredur, who is a real charmer in his backward pigsty of a stronghold. He reminds me of a lecherous King Lear. Uhtred also runs into a Danish warlord who proves to be as devious and loathsome as he looks. In the books his name is Swein of the White Horse, but Butchard has re-named him Skorpa, probably because he doesn’t want us to confuse him with Kjartan’s son Swein from earlier episodes.

And Asser has finally arrived on the scene! One look at his clean face, neat hair and stylish, wrinkle-free grey habit and we just know that this guy and Alfred are going to be kindred spirits. Get used to him. As Uhtred says in The Pale Horseman, “I had just met a man who would haunt my life like a louse.”

Asser was a Welsh monk, later a bishop, and at Alfred’s invitation he became a fixture at the king’s court. In 893 he wrote the Life of King Alfred, and it’s thanks to him that we know as much about Alfred as we do. Uhtred hates him immediately, of course, and the feeling is mutual.

Which brings me back to Uhtred’s buddy, Leofric. At the end of the episode we are left dangling over a cliff-edge of suspense about Leofric. Stephen Butchard has done some skillful snipping and re-weaving of characters and story-line in this episode, and I’m wondering what he is going to offer as motivation for Leofric’s about-face in this final scene.

Am I right in thinking that there is something going on behind Leofric’s pugnacious scowl? Does he have a plan to save both Uhtred and himself? Is he being blackmailed by Odda, who is, after all, his lord? Butchard has veered away from the book here, and we are as astounded as Uhtred by his actions. We’re just going to have to wait until next week, though, to see what, if anything, he has up his chain mail sleeve.