Athelstan was the eldest son of King Æthelred II of England. One of at least 9 brothers and sisters, Athelstan was born sometime in the mid-to-late 980s—we don’t know the exact year—and he died on 25 June 1014 at about the age of 28. His name never appears in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, although for most of his brief life he was recognized as the presumed heir to his father’s throne.

All of the king’s sons were named after earlier kings of Wessex, and all were considered throne-worthy. Athelstan had been named after the king’s great-uncle, King Athelstan (d.939), who had been the first king of Wessex to unite all of England, at least for a time. In the 11th century King Athelstan would have been perceived as the most renowned and important of the royal forebears—even more so than his grandfather Alfred the Great, so it is significant that the king chose that name for his first-born son.

Athelstan’s mother, Ælfgifu, was the daughter of Thored, the ealdorman of Northumbria, and her marriage to Æthelred likely served to strengthen ties between the king and his northern lords. As a result of these northern relations, Athelstan and his brothers would, throughout their lives, have some natural affinity with the nobility of the northern Danelaw.

Their mother Ælfgifu was never crowned queen of England; nor, apparently, was she responsible for the upbringing of her sons. Athelstan and his younger brothers seem to have spent their early years with their paternal grandmother at her estate of Æthelingdene in West Sussex. They don’t appear on the historical record until 993, when Athelstan was about 7. In that year he and three of his brothers signed charters for the first time. Their grandmother, the Dowager Queen Ælfthryth, signed just ahead of them. Presumably, he and his siblings accompanied her to court that year for the first time. On all of the numerous witness lists that follow over the next 20 years Athelstan’s name appears first among his brothers, giving him precedence over them. Nevertheless, upon the death of their mother in 1001, change was in the wind. The king remarried, and the king’s new wife, Emma of Normandy, gave birth to a son, Edward, in 1005. Athelstan would have been about 19, and it is quite likely that the arrival of this new sibling gave rise to certain doubts and questions among the king’s elder sons about the line of succession.

Historian N.J. Higham suggests that although Athelstan perceived himself as the accepted heir to the throne, it is not clear that the king agreed with him. With the birth of Emma’s son, there may have been a serious movement to promote young Edward as next in line for the throne. If so, Athelstan and his brothers would have had good reason to oppose it, possibly causing a rupture between the king and his eldest sons.

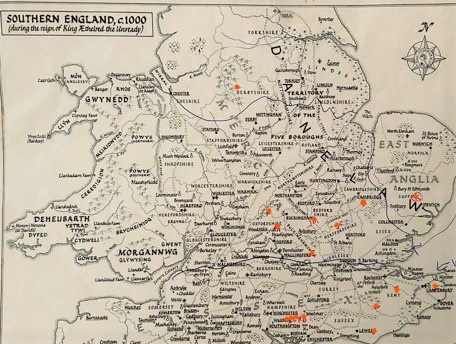

Nevertheless, Athelstan was a wealthy young lord. He owned land in at least 10 counties of south-eastern England, and he was a donor to religious houses at Winchester, Canterbury, Shaftesbury and Ely. He had a household and retainers, and he was friends with a number of significant men in Sussex, Yorkshire, East Anglia, the Five Boroughs and southwest Mercia. And although from 1006 onwards the king excluded some regionally powerful northern kindred from his court, Athelstan retained strong links with them.

Athelstan’s Estates, as mentioned in his will.

Over the next 7 years, increasing military pressure by viking armies led to turmoil in England and disrupted the royal family even more. Athelstan and his brothers would have been involved in their father’s military planning, while their younger half-siblings would have been associated with Emma’s household. By the year 1012 three of Athelstan’s younger brothers had died. In 1013, when Swein Forkbeard and his army overran English defenses—probably with the aid of a secret accord between Swein and the northern lords—Emma and her children fled to Normandy. King Æthelred followed them, but his eldest sons did not.

Emma’s biographer Pauline Stafford suggests that the elder æthelings remained in England, and that when Swein Forkbeard died in early 1014 Athelstan may have made a bid for the empty throne. As it turned out, King Æthelred returned that spring to drive out the Danes and punish the northerners who had supported them. And on the 25th of June, Athelstan died. We don’t know the cause of his death. We only know that his brother Edmund was at his side, and that Athelstan had time to make a will. It is the will that tells us what little we know about the ætheling.

The first thing that he did in that will was to free his slaves—men who were penally enslaved and under his jurisdiction. He bequeathed to various friends and relatives a coat of mail, two shields, a drinking horn, a silver-coated trumpet, a string of fine horses, and eleven swords. One of those swords was apparently a valued family heirloom—the sword of Offa; perhaps the sword that Charlemagne had sent to King Offa of Mercia in 796. It went to Athelstan’s brother, Edmund, who would take his place as the eldest ætheling. Athelstan left properties and estates to his father, to Edmund, to his chaplain, his foster-mother, to various servants and friends, and to several religious houses. I think the bequest that says the most about him was this one: “And I grant to Godwine, Wulfnoth’s son, the estate at Compton which his father possessed.” King Æthelred had confiscated that estate from Wulfnoth; and I can’t help thinking that in bequeathing it to Godwine, Athelstan believed that he was righting a wrong.

Athelstan was buried at the Old Minster in Winchester. He was the first non-king to be buried there in over 90 years. It’s possible that his remains are among the royal bones that lay for centuries in the mortuary chests above the cathedral altar and that are now under study. If so, we may one day learn more about this royal son who never became king.

The mortuary chests in Winchester Cathedral.

Sources:

Æthelred the Unready, Levi Roach

The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England, Ed. Michael Lapidge

The Death of Anglo-Saxon England, N. J. Higham

English Historical Documents, D. Whitelock

Queen Emma & Queen Edith, Pauline Stafford

A fascinating read, and it is those details, the possible righting of a wrong, that gives insights into their possible characters…Now immediately I think of him as an honourable man…as he is in your novels of course…

Hilary :)