Emma of Normandy, Dowager Queen of England, died on 6 March, 1052, in Winchester. She was only the second woman to be crowned queen of all England, and the only woman ever to be crowned queen of England twice. For 50 years, through the reigns of her two husbands, her two stepsons and her two sons, she was a significant figure in English politics.

Emma of Normandy, Dowager Queen of England, died on 6 March, 1052, in Winchester. She was only the second woman to be crowned queen of all England, and the only woman ever to be crowned queen of England twice. For 50 years, through the reigns of her two husbands, her two stepsons and her two sons, she was a significant figure in English politics.

Her first marriage in 1002 was to King Æthelred II—a widower with 10 children, several of them adolescent sons who must have been more than a little alarmed to see dad take a new bride who was young enough to be his daughter and who would likely give him sons to one day vie with them for England’s throne. On Emma’s arrival in England, she surely had to negotiate some thorny family relationships at the same time that she was learning to navigate the sometimes deadly interplay between the king, the nobles, and the ecclesiastics who jockeyed for power in 11th century England. And, along with everyone else, she had to avoid the marauding viking armies who regularly ravaged the kingdom.

A modern interpretation of Queen Emma from my novel The Price of Blood.

The years of that first marriage could not have been easy ones for the young queen, but Emma was well prepared to face them. She appears to have been a polyglot who spoke Norman French, had probably learned Danish from her mother, and no doubt picked up the English tongue quickly if she didn’t know it already. There is evidence that she could read Latin, which was the language of literature and law in England and the rest of Europe. Before she was 20 years old, she was a wife, a queen, a stepmother, a mother, a landowner, a patron of the church and the arts, and the manager of a vast household.

By 1013, though, with England at all-out war against the invading Danish king Swein Forkbeard–and losing–Emma was forced to abandon her many English properties (and their incomes) and flee to Normandy with her children.

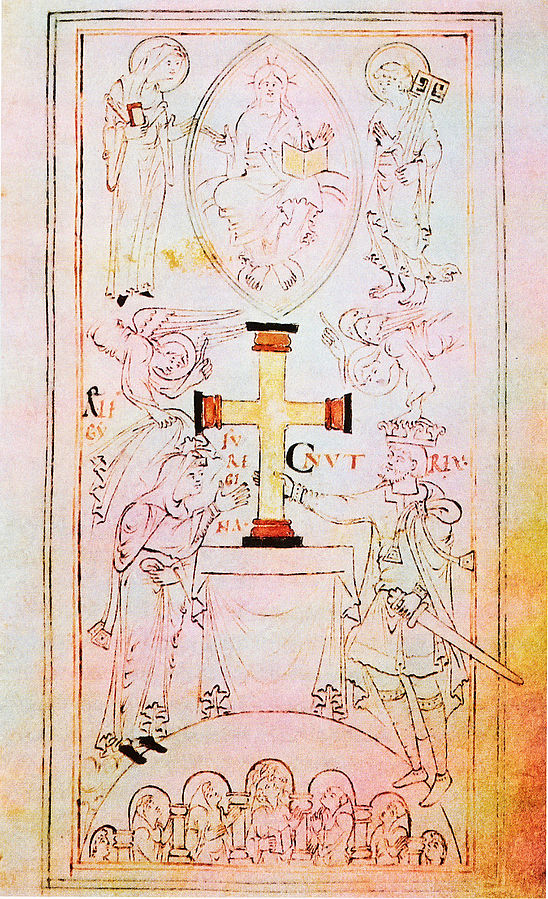

Emma and her children flee war in England. From the 12th c Life of Edward the Confessor (Wikimedia Commons)

There she persuaded her brother, Duke Richard II, to offer refuge to her husband and his court when no one could possibly have estimated how long such an arrangement might have to last. Once again there must have been some family tensions to navigate.

Swein died suddenly, though, in early 1014 and Æthelred, invited back to England, ousted Swein’s son Cnut and the remnants of his viking army that were scattered all across the kingdom. Emma returned to England as well, but there were more trials to face. In 1015, while the king had some of his powerful lords murdered and his eldest son responded by rebelling against him, (more family strife–it never got easy), the Danish prince Cnut, determined to win himself a kingdom, returned with a massive army. In 1016, probably to no one’s sorrow, King Æthelred died and Emma’s stepson Edmund, now the king, took up the fight against the Danes. When Cnut laid siege to London, Emma was trapped inside the city, and there are indications that the widowed queen played a role in the citizens’ successful resistance, although we cannot be sure. Stories differ. What is certain is that her stepson, King Edmund Ironside, lost a major battle at Assandun in late 1016 and died soon after. When the dust settled, in mid-1017, Emma married Cnut, the victorious new king of England, and her second reign as queen began.

Cnut offers marriage to Queen Emma. Fredericksborg Castle, Denmark

Emma made certain that her children by Æthelred—Edward (12), Godgifu (7), and Alfred (4), were given refuge in Normandy with her brother. As a result, the relationship between Emma’s children and their Norman kin would be very strong, and in 1066 their cousin William would use those ties to bolster his claim for the English throne, and we all know how THAT turned out. But that was way in the future—there would be 4 kings of England between the reigns of Cnut and William the Conqueror.

As queen consort and advisor to Cnut, and as patron to churches and abbeys in England and in Europe, Emma was even more powerful during Cnut’s reign than she had been during Æthelred’s. According to Emma, it was a marriage of equals.

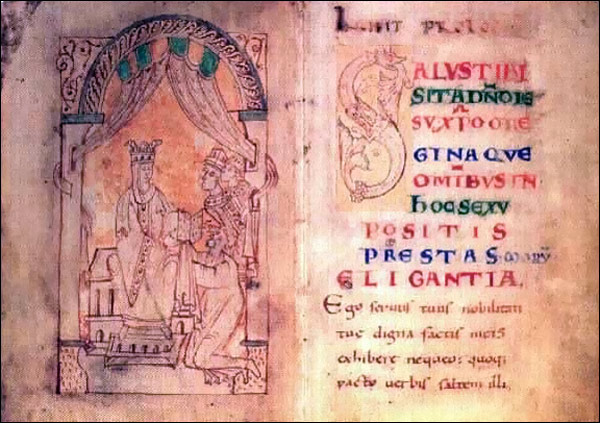

Queen Emma & King Cnut. New Minster Liber Vitae, 1031. British Library, Stowe 944, fol.6. (Wikimedia Commons)

Cnut’s hold on England was eventually secure enough that he could journey to Rome and lead armies in Scandinavia, leaving England in the hands of regents, one of whom was likely his queen, Emma. She and Cnut had two children: Harthacnut, who would become king of Denmark and England; and Gunnhild who would marry the son of the Holy Roman Emperor.

Still, there must have been some tensions within the royal family itself. When Cnut married Emma he already had a wife, Ælfgyva of Northampton, who had given him sons and who was lurking somewhere in England or Scandinavia. Aware of this problem from the start, Emma demanded a pre-nup from Cnut guaranteeing that any sons she might have would be his heirs; but when Cnut, whose empire included both England and Denmark, died in 1035, the only one of his sons in England was Ælfgyva’s boy, Harold.

Urged by his mum, Harold immediately presented himself as the claimant to Cnut’s English throne, earning the nickname Harefoot. Because Emma’s son, Harthacnut, was in Denmark preparing to defend it against imminent invasion by the Norse and the Swedes, the English magnates decided to divide England in half: Harald to govern north of the Thames, where his support base was, and Emma to govern as regent for Harthacnut in the south. To complicate things even more, Emma’s sons by Æthelred arrived in 1036 to stake their own claims to the throne, and the outcome was disastrous. Alfred was captured and killed by men loyal to Harold, Edward fled back to Normandy, and Emma was driven out of England by Harold, taking refuge with her noble kin in Bruges.

Even in exile, though, Emma was working to place one of her sons on the throne of England. She summoned Edward and they discussed it, but his younger brother’s tragic fate at English hands convinced him that he wouldn’t have support from the English. In 1040 Harthacnut joined Emma in Bruges, fully prepared to make the attempt to oust Harold, his half-brother, from the English throne. Just as Emma and her son were about to lead an invasion force to England King Harold Harefoot conveniently died. Harthacnut, age 22, claimed the crown of England with Queen Emma beside him to offer support and counsel.

Emma was now mater regis, mother of the king, and once again a significant force in English politics. In 1041 Harthacnut invited his half-brother Edward to England from Normandy. This was probably Emma’s suggestion, and it may have been because Harthacnut was not well.

Harthacnut. Photo credit, British Library (Wikimedia Commons)

For a time, Emma was once more a powerful political figure, second only to her sons. We know this because of her signature on charters and because she commissioned a book—a remarkable example of 11th century political spin that related events in England, from the war with Swein Forkbeard in 1013 to the beginning of Harthacnut’s reign in 1040, as Emma wanted them remembered. Known now as the Encomium Emmae Reginae, it might have been read aloud as entertainment at court, the Latin translated aloud into Danish, Flemish, French and Old English.

Emma receives her copy of the Encomium Emmae Reginae from the writer as her sons look on. (Wikimedia Commons)

But in 1042 Harthacnut died, and Edward, almost 40 years old, became sole ruler of England. He did not want any help from his formidable mother, thank you very much, and it especially irritated him that mummy had control of the royal treasure. In 1043 he rode to Winchester to confront her, taking with him three powerful earls and a force of armed men. (Did I mention that Emma was formidable?) With their help he confiscated the royal treasure and divested his mother of most of her lands, ordering her to live a quiet life; for a while she did. But she was back at court in 1044, perhaps having persuaded Edward that he had been too harsh in his actions toward her. Eventually, though, her name disappears from the witness lists and it must be presumed that, after Edward married in 1045, Emma finally decided to step aside. (Two queens is always one too many. More family strife.) Maybe she hoped to retire and help raise the king’s children. If so, she must have been awfully disappointed when there weren’t any.

Emma outlived all of her children except for her son, Edward the Confessor, and a daughter, Godgifu–both children of AEthelred. She was buried at the Old Minster in Winchester next to Cnut and Harthacnut, and when that building was pulled down their bones were preserved with others in mortuary chests in Winchester Cathedral.

Wikimedia Commons

In the past decade Queen Emma, for centuries relegated to the footnotes of history, has been re-discovered. Helen Hollick based her novel The Forever Queen on Emma’s life story. I built my Emma of Normandy Trilogy around her years as Æthelred’s queen. Now, British composer William Blows has written a symphony titled Queen Emma which celebrates her life. She is no longer a forgotten queen. And in Winchester, the bones in those ancient mortuary chests are being examined to see what DNA testing can tell us about the royals of Anglo-Saxon England, including the formidable queen, Emma of Normandy.

The mortuary chests in Winchester Cathedral.

Sources:

Queen Emma & Queen Edith: Queenship and Women’s Power in Eleventh Century England, Pauline Stafford

Cnut the Great, Timothy Bolton

Encomium Emmae Reginae, ed. Alistair Campbell

‘Sons and Mothers: Family Politics in the Early Middle Ages’. Pauline Stafford. In Mediaeval Women, ed. D. Baker

‘Aelfgifu of Norhtampton: Cnut the Great’s Other Woman’, Nottingham Medieval Studies, LI (2007), Timothy Bolton

Predatory Kinship and the Creation of Norman Power, 840-1066, Eleanor Searle

‘The Aethelings in Normandy’, Anglo Norman Studies, vol. 13, Simon Keynes

Harthacnut, The Last Danish King of England, Ian Howard

Absolutely an amazing read. Thank you for the post.

I hope this makes it to a TV series and that they stick to the facts. This story needs no embellishment. I want factual story, great scenery and authentic costumes. Is this too much to ask?

Hi Lora. Well, I would certainly watch such a series. But what you are asking for is a documentary, or at the very least, a docu-drama. And the minute that you dramatize something, you have to include story arc, conflict, rising tension, and dialogue. Dialogue! If you want your series to stick to the facts, you can’t have dialogue because we don’t know what these people said to each other a thousand years ago. In order to have dialogue, you have to make it up, and before you do that you have to take a stance on how these people related to each other when nobody can be absolutely certain about that. Even historians have to make guesses about what happened because the historical documents we have don’t always agree. For example, in my essay up there I’ve written that Emma was trapped in London when the city was under siege, based on a Norman chronicle (William of Jumieges), on later Icelandic poetry (which is always difficult to interpret), and on the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’s comment that Cnut “had her fetched.” But Emma’s Encomium says that Cnut searched far and wide for a queen, and found her in Normandy. Anyone writing Emma’s history has to decide which story to believe. And then you’d have to sell the series to a producer who would demand that it had all of the things I mentioned above, (story arc, etc.), but also a love interest and probably more things that I can’t even imagine. And that all means ’embellishment’. So, unfortunately, I don’t think you can expect to see this story on TV any time soon – at least, not the way you’d like to see it done. It’s not possible.

I think that Emma’s life was as fantastic as Eleanor of Aquitaine…I have some doubts: why Emma exiled in Flandres and not in Normandy with Edward? Had Emma ever met her nephew William,the Conqueror? Is it possible Emma had influenced the marriage of William and Matilda of Flandres?

Oh my goodness. Very good questions. Emma probably avoided Normandy in 1037 because it was in turmoil. Duke Robert (Emma’s nephew) had died in 1035 on his way home from Jerusalem, leaving an 8 year old son, William, as the heir to his duchy. Well, you know what happens when a child is ruler–pandemonium. There were nobles revolting in Normandy. (3 of Williams guardians were murdered.) Emma’s brother, an elderly Archbishop Robert, died in 1037. No help for her there. It’s impossible to know exactly what Edward’s situation was in Normandy at that time. For all we know, he may have been living in an abbey at Fecamp or Jumieges, keeping his head down after the failed attempt to return to England. He was not likely in a position to offer hospitality to his mother. Bruges was a good option, and Emma probably had good contacts with the court there. Emma’s niece, Eleanor, (age about 27) was the step-mother of Count Baldwin V (he was 25), and Baldwin’s wife was the daughter of the King of France. They could accommodate Emma in the style to which she was accustomed. She may have been to Bruges before (on her way to Rouen in 1013). Bruges was a hopping place. Very wealthy! Also, it was only a day’s sail from England – closer, really, than Rouen. And it was between Denmark and Normandy, so Emma could get news of events from either place. It was a smart choice. Did William the Conqueror meet Emma? He was in England in 1051, the year before Emma died. It’s possible he went to see her then. I couldn’t even begin to guess if she had any influence in his marriage to Mathilda. I suspect that was all William’s idea. One of my books indicates that there was a strong emotional bond between William and Mathilda. It was never merely a political union. Whew! Questions answered!

Fantastic!thank you so much. I think the third book Will be the best! So much events! I really love that time in History. And I love all your posts. Many kisses from Brazil.

A very enjoyable romp through turbulent times. You do not mention the episode with Eadwig, the last surviving male heir of Æthelred in 1017. The same year Emma marries Canute, Eadwig is declared “outlaw”. Eadwig manages to get back into Canute’s favour before being murdered by persons unknown. The next in line to the English throne ( in Emma’s eyes) is her first born, Edward. Two poisonings later and Edward is indeed King without even having the bother to be “voted” into office by the Witan. Umm, a very formidable woman indeed.

Hello Kevin. Thank you for your comment. No, I did not mention Eadwig, mostly because he has little to do with Emma. His interaction, I believe, was with Cnut. Timothy Bolton has speculated that in 1017 Eadwig and Eadric Streona may have been planning some rebellion against Cnut, who got wind of it and the result was Eadwig’s banishment and Eadric’s execution. But the records from that period are so vague that you can read many different possibilities into what might have taken place, as you have with the suggestion of poisonings. You seem to be implying that Emma poisoned or ordered poisoned both Harald Harefoot (she was in Flanders) and Harthacnut (her son by Cnut). I find it difficult to believe that myself. There is no evidence of it, and I don’t know of any scholarship that suggests that. The evidence, I think, seems to point to a possible genetic weakness in Cnut’s line since every single one of his sons died fairly young, and fairly suddenly. (Swein Cnutson about age 30, Harald about age 30, Harthacnut not yet 30. His daughter by Emma died of an illness in her 20’s). We don’t know what killed Cnut, only that he died suddenly when he was in his 40’s. Yes, people think poison whenever there is a sudden unexplained death, so I see where you are coming from, but to claim that Emma poisoned one son to put the other on the throne (and the one she did not get along with very well) is a theory that I’m not willing to entertain.

Is the final book of this trilogy finished?

I’ve finished a draft of it, but it needs more work and I have my nose pressed to the grindstone every day to complete it!